Introduction

CSIT periodically releases challenges to ‘create awareness on the various tech focus areas of CSIT’. The topic of their CNY 2024 mini-challenge was mobile reverse engineering. I had minimal experience in this topic but I decided to give it a shot nonetheless. The following is an account of my thought process, how I understood the concepts I encountered, and how I solved the problems I encountered along the way (spoiler: G _ _ _ _ e).

The challenge

The task was to crack a provided apk to retrieve a message (the flag). In the problem statement, CSIT provided a suggested approach and some useful resources. Specifically, there were some writeups about SSL pinning/unpinning and links to writeups about using Burpsuite and Frida - tools commonly used to perform SSL unpinning.

Loading the apk

To start, I set up an Android Virtual Device (AVD) in Android Studio to serve as my emulator. I chose a Pixel 6 Pro running Android 13.0 x86_64 (with ‘Default Android System Image’ type NOT ‘Google APIs’ - the latter is unrooted).

I then ran into my first problem: upon startup, the Pixel only displayed a black screen with nothing on it. I rebooted the emulator a few times to no avail. After consulting Google, I changed ‘Graphics’ to ‘Hardware - GLES 2.0’ and RAM to 2048MB in the advanced settings for the device and this solved the issue.

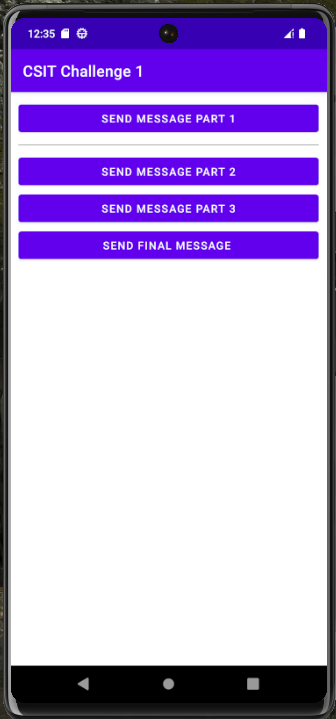

I downloaded the target apk and installed it on the Pixel by simply dragging and dropping it into the emulator window. This is what the app looks like:

Clicking on any of the purple ‘send ___’ buttons seemed to do nothing except change the button’s colour from purple to green.

A (futile) attempt at static analysis

My initial approach was to perform some static analysis on the apk. Decompiling the apk (using apktool with the d option and -s and -r flags) gave me a file called classes.dex, which I learnt essentially contained all the application’s logic.

I then used dex2jar to convert classes.dex into a jar file, which I then opened in JD-GUI for analysis. The jar file contained a file called MainActivity.class, which I figured contained the bulk of the application logic. The structure of MainActivity.class is as follows:

(Functions end with (); the rest are classes. ... denotes a set of 3 functions create(), invoke(), and invokeSuspend() (but not defined identically for each class))

MainActivity

├─ onError()

├─ onStart()

├─ onSuccess()

├─ decrypt()

├─ getMediaTypeJson()

├─ onCreate()

├─ sendOkHttpPinned()

├─ sendOkHttpPinnedd()

├─ sendOkHttpPinneddd()

├─ sendUnpinned()

├─ OnCreate

│ ├─ OnCreate()

│ ├─ invoke()

├─ OnError

│ ├─ OnError()

│ ├─ create()

│ ├─ invoke()

│ ├─ invokeSuspend()

├─ OnStart

│ ├─ OnStart()

│ ├─ create()

│ ├─ invoke()

│ ├─ invokeSuspend()

├─ OnSuccess

│ ├─ OnSuccess()

│ ├─ ...

├─ sendOkHttpPinned

│ ├─ sendOkHttpPinned()

│ ├─ ...

├─ sendOkHttpPinnedd

│ ├─ sendOkHttpPinnedd()

│ ├─ ...

├─ sendOkHttpPinneddd

│ ├─ sendOkHttpPinneddd()

│ ├─ ...

├─ sendUnpinned

│ ├─ sendUnpinned()

│ ├─ ...

What stood out to me was the multiple definitions of the sendOkHttpPinned(d(d)) class / function. I thought of digging deeper into the code but it was quite complex and I wanted to explore the other resources provided by CSIT before potentially wasting time here.

SSL (un)pinning

As mentioned, the information provided suggested that extracting the flag involved bypassing SSL pinning.

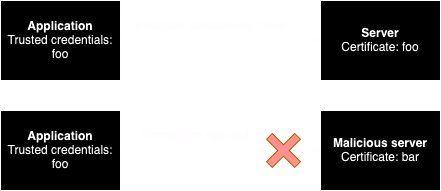

SSL pinning is a security measure which checks the SSL certificate of the server contacted by the app against a trusted cert hard-coded in the app (either the cert data itself or its hash). This feature verifies that the target server is legitimate and can be trusted, and thwarts man in the middle attacks, amongst others.

In the writeup for this challenge, CSIT had thankfully provided a link to a step-by-step guide for bypassing SSL pinning on Android applications using Frida and Burpsuite.

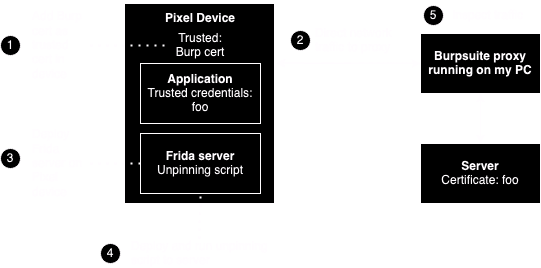

To perform dynamic analysis, we want to analyse the outbound requests made when the app is interacted with, which we can do with Burpsuite. Burpsuite has a proxy feature which will allow us to intercept, analyse, and modify network traffic to and from the Pixel, but we will first need to retrieve Burpsuite’s SSL certificate and get the Pixel to trust it before the Pixel will ‘communicate’ with Burpsuite.

Frida is a ‘dynamic instrumentation toolkit’ which will allow us to deploy a server on the Pixel and deploy a script on that server which will help us bypass the SSL pinning. In other words, we can deploy a Frida script onto the device to get the target apk to the the Burp certificate we had deployed previously, hence bypassing SSL pinning (refer to the ‘What is not SSL pinning’ section in this document for more information about the role of Frida and Burpsuite).

Therefore, the approach is as follows:

(note that the step numbers here don’t correspond to the step-by-step guide)

Setting up the proxy in Burpsuite

The first step was to get the Pixel device to trust the Burp cert. CSIT provided some instructions on how to do it but I found an easier way courtesy of this tutorial on YouTube. To get the Burp cert, I launched a browser from the Burpsuite app (Proxy > Intercept > Open Browser) and navigated to http://burp. Clicking on ‘CA Certificate’ in the top right hand corner downloaded the cert (I made sure to save it with the ‘.cer’ extension). All that remained is to follow the steps in the aforementioned video from 5:58 onward.

The second step was to direct the Pixel’s outbound traffic to the Burp proxy. The video also covered how to do this (from 4:06 onward), although I realised that for it to work I had to enter the actual IP address of my PC as the proxy host instead of the localhost address like in the video.

I verified that steps 1 and 2 were done correctly by checking if Burpsuite intercepted traffic when I navigated to different webpages using the browser on the Pixel. Upon running the target application again I realised that instead of turning green like before, the purple buttons turned red when tapped. No traffic was intercepted by Burp and the emulator shows that some kind of SSL Pinning exception was raised. This was, however, expected because the SSL certificate of Burp didn’t match the info of any trusted SSL certs stored in the application and hence the application ‘refused to communicate’ with Burp.

Performing the bypass with Frida

Steps 3 and 4 were also quite straightforward and were easily accomplished by following the aforementioned step-by-step guide provided (the only difficulty I encountered was self-inflicted, when I downloaded the devkit instead of the server from the Frida github page).

When executing the unpinning script on the server, I encountered a FileNotFoundException which reported that a file called cert-der.crt was missing from a specified folder. I solved this by using adb to launch a shell in the web server and copying the Burp cert from the ‘Downloads’ folder to the specified folder, renaming the cert to the appropriate name.

Retrieving the flag

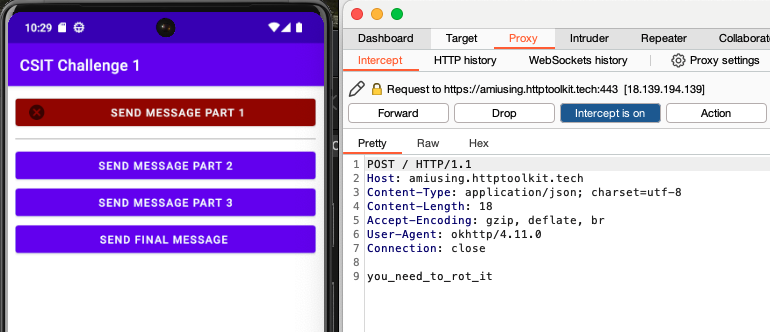

After running the Frida bypass script (and with intercept in Burpsuite turned on), I tapped on the ‘send message part 1’ button and observed that a HTTP POST request was intercepted. The body of the request contained a string of interest:

I tried to tap on the other ‘send message’ buttons but no traffic was intercepted. In fact, the emulator showed that some SSL-pinning related exception occurred whenever those buttons were tapped. The SSL pinning bypass worked for only 1 out of 4 buttons.

I eventually did manage to resolve this, but I did so completely accidentally. I essentially thought that the string in the request body was a clue for bypassing pinning for the other 3 buttons, so I was just searching random combinations of the words ‘SSL pinning’, ‘certificate’, ‘bypass’, and ‘rotation’ (because of rot). I eventually came across another tutorial for SSL pinning bypass using Frida. This tutorial used a different bypass script (frida-multiple-unpinning) from the one used in the walkthrough provided by CSIT (Universal Android SSL Pinning Bypass with Frida).

I replaced the old script with this new script and found that everything worked properly, i.e., that the new script successfully bypassed SSL pinning for all buttons. When each button is pressed, a HTTP POST request is made (which is intercepted by Burp), and the body of each request contained a string. Only upon putting all 4 strings together did I realise that ‘rot’ referred to the Caesar cipher, which one of the strings, the flag, was encrypted with!

Retrieving the flag was as simple as putting the encrypted string into a Caesar cipher brute force decryptor tool (which tried all possible rotation amounts) like this one.

Why did replacing the bypass script work?

In other words, what was the difference between the first script (the one used in the CSIT provided walkthrough) and the second script (the one I found)?

My best guess is this: since these scripts bypassed SSL pinning by overriding the functions performing the checks during runtime, perhaps the second script catered towards implementations of SSL pinning which were used in the application logic which just weren’t handled by the first script.

The second script attempts to bypass different implementations of SSL pinning, such as OkHTTPv3, Trustkit, Appcelerator etc. On the other hand, the first script looks like it only tries overloading pinning implemented with the javax.net.ssl library. If we look at the import statements in MainActivity.class in the source code, we can see that okhttp3.CertificatePinner is used. This corroborates the idea that the second script had code to bypass implementations of SSL pinning which the first script lacked.

Conclusion

This was an adequately challenging but still fun challenge. Even though resources and a step-by-step guide was provided, effort still had to be put in to try to understand the technology involved and the approach employed in the walkthrough.

The previous CSIT challenge I attempted was the TISC CTF. Given that I didn’t even get past the first (and supposedly easiest) level back then, I’m happy that I managed to complete this challenge in good time :-).

On to the next one!