Introduction

Krypton is centred around cryptography. To me, the most challenging aspect of this wargame was the need to create custom tools and/or perform manual decryption. For example, in one of the levels I spent three hours trying to code a frequency analysis tool, before giving up and using an existing online tool - this helped me solve the problem in less than a minute. The concepts covered are relatively straightforward to understand, but putting them into practice was rather tedious and/or complicated (without the online tools).

Challenges

| Level 0 |

| Level 1 |

| Level 2 |

| Level 3 |

| Level 4 |

| Level 5 |

| Level 6 |

Level 0

The password can be decoded in the terminal using the command

echo "S1JZUFRPTklTR1JFQVQ=" | base64 --decode

and we can connect to the server by running

ssh krypton1@krypton.labs.overthewire.org -p 2231

and entering the decoded password when prompted.

Level 1

We see two files in /krypton/krypton1, README and krypton2. The former explains that to get the ssh password for krypton2, we need to decipher the string in the file krypton2, which is encrypted using the ROT13 cipher, where every character in the plaintext becomes the alphabetical chracater 13 positions ahead of it (with wrap-around).

This can be easily done by hand, but to save time I just used this online tool to decode the ciphertext.

Level 2

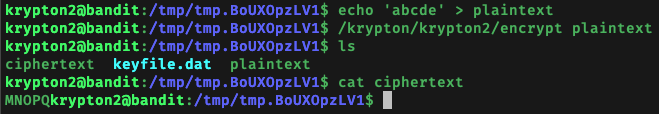

We aren’t able to directly access the key used to encrypt the password for krypton3, but we do have access to the program which uses that key to encrypt the plaintext. This means that to figure out the key we can just ask the program to encrypt ‘abcde’ and analyse the produced ciphertext to retrieve the ‘rotation factor’, i.e. how much each character is rotated, and from there deduce the key used:

We see that ‘abcde’ is encrypted to become ‘MNOPQ’. From this we can deduce that ‘f’ becomes ‘R’, ‘g’ becomes ‘S’, ‘h’ becomes ‘T’, etc.

We can also hence deduce that the ‘rotation factor’ is 12, since each character is substituted by the one 12 positions ahead of it in the alphabet.

With this in mind, there are two ways we can recover the plaintext password: either shift each character in the ciphertext backwards by 12 characters, or shift each character in the ciphertext forwards by 14 characters (resulting in a total of 26 forward shifts, i.e. effectively no shift at all).

I chose the first method, and used this online tool instead of working it out manually to save time.

Level 3

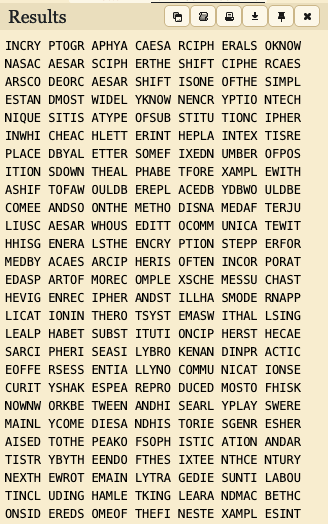

The password for krypton4 is encrypted using a substitution cipher, but no longer a simple shift / rot cipher. We can use found1, 2, and 3 to perform frequency analysis to try to reverse engineer the key used for substitution.

I will be using this for frequency analysis and this substitution decoder tool to perform guess and check. I will use the former to derive guesses for plain $\leftrightarrow$ ciphertext mappings and then insert the mapping into the substitution decoder tool to see whether the resultant plaintext made sense and thus decide whether the mapping was right or wrong.

(There is actually a tool on the same site that automatically decrypts the ciphertext but I wanted to try performing the anlaysis manually, only using the substitution and frequency analysis tools to cut out the ‘meaningless’ tedious work.)

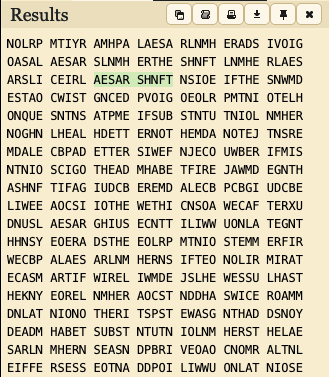

I compiled found1, 2, and 3 and performed the frequency analysis on the ciphertext using the tool. These are the reults:

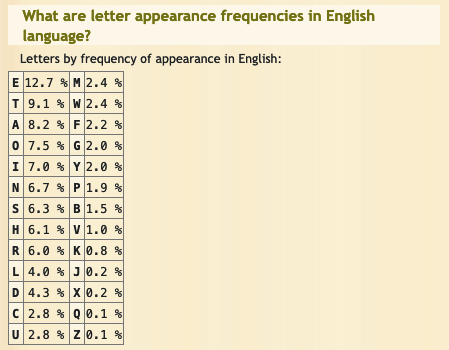

The frequency analysis tool also provides a table showing the frequency of appearance in typical english language texts:

As a first pass, I decided to just match the letters based on their relative frequency. For example, ‘S’ appeared the most in the ciphertext, and according to the expected frequencies table, ‘E’ appears the most in english texts. Thus, I entered the plain ‘E’ to coded (cipher) ‘S’ mapping into the decoder tool. ‘Q’ appeared the second most in the ciphertext, and ‘T’ appears the second most in typical english texts, and thus I entered the plain ‘T’ to coded ‘Q’ mapping into the decoder tool.

I did the same for the other characters, but the resulting decoded text was unfortunately gibberish.

I then decided to enrich my data using bigram analysis, which calculates the frequencies of adjacent pairs of characters in text such as ‘TH’, ‘HE’, and ‘ER’.

The two most frequent bigrams in the ciphertext are ‘JD’ and ‘DS’ and this perfectly matched the most frequent bigrams in typical english texts: ‘TH’ and ‘HE’. I thus made the following changes to the mappings in the decoder:

- plain ‘T’ $\leftrightarrow$ coded ‘J’ (previously ‘Q’)

- plain ‘A’ $\leftrightarrow$ coded ‘Q’ (previously ‘J’)

- plain ‘H’ $\leftrightarrow$ coded ‘D’ (previously ‘C’)

- plain ‘R’ $\leftrightarrow$ coded ‘C’ (previously ‘D’)

I then noticed that bigrams ‘ER’ and ‘RE’ occured quite often in plaintext, and ‘SN’ and ‘NS’ are amongst the most frequent occuring bigrams in the ciphertext. Since our current guess is that cipher ‘S’ is plain ‘E’, these bigrams matched up perfectly, i.e. cipher ‘SN’ and ‘NS’ are likely plain ‘ER’ and ‘RE’. I hence made the following changes:

- plain ‘R’ $\leftrightarrow$ coded ‘N’ (previously ‘C’)

- plain ‘N’ $\leftrightarrow$ coded ‘C’ (previously ‘N’)

Based on current knowledge, plain ‘E’ is probably coded ‘S’. The bigram ‘ES’ occurs 7th most commonly in plaintexts, and I guessed that the corresponding ciphertext bigram is ‘SU’, which occured 4th most frequently in the ciphertext. Therefore, I made the following changes:

- plain ‘S’ $\leftrightarrow$ coded ‘U’ (previously ‘G’)

- plain ‘O’ $\leftrightarrow$ coded ‘G’ (previously ‘U’)

Decrypting with the current mappings, I got:

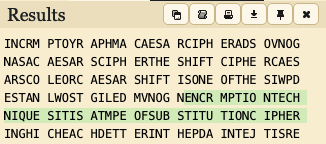

The highlighted text seems to possibly be ‘caesar shift’. I changed the relevant mappings in the correspondences and got the following:

The highlighted seems to be ‘caesar cipher’ and the last line in the screenshot seems to contain ‘substitution’. After making the necessary changes, I got:

I figured the highlighted text is meant to read ’encryption techniques. it is a type of subsitution cipher…’, and hence made the necessary changes.

I kept repeating this process, guessing words and revising the mappings, until I recovered the full plaintext:

The found texts are a writeup about the Caesar cipher, Shakespeare, and a snippet from ‘The Gold-Bug’ from Edgar Allan Poe. The key used for substitution is:

QAZWSXEDCRFVTGBYHNUJMIKOLP

which we can easily use to decode the contents of krypton4.

Level 4

This challenge requires us to break a Vigenere cipher. One method is to break the ciphertext up into n blocks, where n is the keysize (in this case 6) and perform frequency analysis on each block. This post details how it can be done.

I tried to write a script to implement this method, but even though I was able to generate the blocks and figure out the top few most likely keys based on simple frequency analysis, I couldn’t figure out an effective and efficient way to analyse the correctness of the results:

import itertools

KEY_SIZE = 6

cipher_text = '<omitted>'

MOST_FREQUENT_LETTERS = 'ETAOINSHRD'

N = 5

def strip_ciphertext():

temp = ''

global cipher_text

for c in cipher_text:

if c == ' ':

continue

else:

temp += c

cipher_text = temp

def make_blocks(blocks):

for index in range(KEY_SIZE):

blocks[index] = ''

count = 0

for letter in cipher_text:

blocks[count % KEY_SIZE] += letter

count += 1

def calculate_frequencies(text):

frequencies = dict()

for letter in text:

if letter not in frequencies.keys():

frequencies[letter] = 0

frequencies[letter] += 1

return sorted(frequencies.items(), key=lambda item: item[1], reverse=True)

def populate_guesses(frequencies):

guesses = []

for index in range(KEY_SIZE):

guesses.append([])

for i in range(N):

plain = MOST_FREQUENT_LETTERS[i]

most_frequent_in_cipher = frequencies[index][0][0]

diff = ord(most_frequent_in_cipher) - ord(plain)

diff = diff + 26 if diff < 0 else diff

guesses[index].append(diff)

return guesses

def is_possible(text):

words = ['VIGENERE']

for word in words:

if word not in text:

return False

return True

def decrypt(guesses):

keys = list(itertools.product(*guesses))

for k in keys:

plaintext = ''

count = 0

for c in cipher_text:

plain_ord = ord(c) - k[count % KEY_SIZE]

if plain_ord < ord('A'):

plain_ord += 26

plaintext += chr(plain_ord)

count += 1

if is_possible(plaintext):

print(plaintext)

blocks = dict()

frequencies = dict()

strip_ciphertext()

make_blocks(blocks)

for key in blocks.keys():

frequencies[key] = calculate_frequencies(blocks[key])

guesses = populate_guesses(frequencies)

decrypt(guesses)

This script calculates the N most likely characters for each index of the key and uses all possible keys to decrypt the ciphertext.

After working on the script for 3 hours, I decided to just use an online tool to derive the key, which took me less than 30 seconds. Using this key, the contents of krypton5 are easily decrypted.

Level 5

This challenge is similar to the previous one in that a Vigenere cipher is involved. The only difference is that the length of the key is unknown. The length of the key can be found using Kasiski analysis, where the distances between the repeating sequences of characters in the text are used to derive the various possible key lengths (which are factors of the distances between the repeating sequences). This article explains this concept well and provides a tool for key length analysis and even decryption.

Using this tool, I deduced that the key length is most likely 9 characters long. I then used the Vigenere decoder tool from the previous level to figure out the key, which led to the decryption of krypton6.

Level 6

The hints reference 8 bit LFSRs, and I found this article explaining this concept. The article, however, did not explain how to break encryption methods which use this.

From the README for this challenge, I figured that the ciphertext was generated using:

plain XOR (key AND random) = cipher

and thus thought that (key AND random) could be recovered using cipher XOR plain. However, after doing some tests, I realised that the (key AND random) values were different for different values of plain, even though the same plaintext always yielded the same ciphertext. In a way, this indicates that the (key AND random) values are somehow determined by the plaintext.

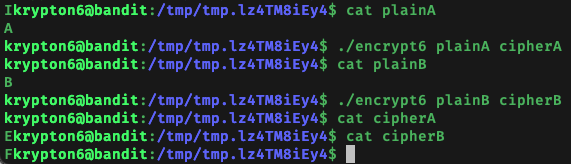

My next approach was to brute force krypton7 by executing a known plaintext attack. I began by encrypting the single characters ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, ‘D’, and ‘E’ to see if there were any patterns in the resultant ciphertext :

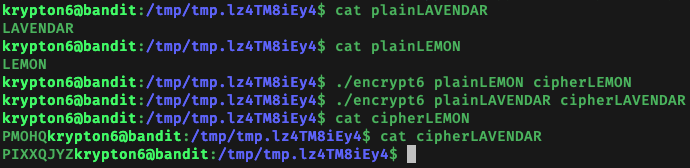

I found that ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, ‘D’, ‘E’ encrypts to ‘E’, ‘F’, ‘G’, ‘H’, ‘I’ - which shows that the plaintext character is ‘shifted’ by 4. Since the first letter of krypton7 is ‘P’, the first character of the correspnding plaintext should be ‘L’, which I verified by encrypting the single character ‘L’. I further verified that encryption of the first character of the plaintext is independent of the subsequent characters in the plaintext by encrypting different words that start with ‘L’ and verifying that the resultant ciphertexts began with ‘P’:

We can now do something similar to guess that next character of the krypton7 plaintext. I encrypted ‘LA’, ‘LB’, ‘LC’ and found that the resultant ciphertexts were ‘PI’, ‘PJ’, and ‘PK’ respectively - a ‘shift’ of 8. Since the second character of krypton7 is ‘N’, I guessed and verified that the second character of the corresponding plaintext is ‘F’.

Instead of repeating this manual process for the other characters of krypton7, I decided to write a bash script to do it:

#!/bin/bash

target='PNUKLYLWRQKGKBE';

target_length=${#target};

current_known='';

current_known_length=0;

while [ $current_known_length -lt $target_length ];

do

starting_length=$current_known_length

target_substring=${target:0:$current_known_length + 1}

for i in $(seq 65 90);

do

letter=$(printf "\x$(printf %x $i)")

guess="${current_known}${letter}"

plain_filename="plain${guess}"

cipher_filename="cipher${guess}"

echo $guess > $plain_filename

./encrypt6 ${plain_filename} ${cipher_filename}

result=$(cat ${cipher_filename})

rm ${plain_filename}

rm ${cipher_filename}

if [ "$result" = "$target_substring" ]; then

current_known="${guess}"

((current_known_length++))

break

fi

done

if [ $starting_length = $current_known_length ]; then

echo "Error: no correct guesses"

break

fi

done

echo "The unencrypted target string is: ${current_known}"

This script automates the process described above: it appends a possible character (‘A’ to ‘Z’) to the current known plaintext string, encrypts the whole thing, and compares the result to the relevant substring of the krypton7 ciphertext. If they match, then that possible character is appended to and considered part of the known plaintext string and the process repeats for the next character in the ciphertext. If the result doesn’t match, then the next possible character is considered. This process repeats until all characters in krypton7 have been guessed and the plaintext for krypton7 is recovered.

Using this method, we didn’t need to figure out how the random numbers were generated during the encryption process nor the key involved. Running this quickly yielded the plaintext of krypton7.