Introduction

This is my writeup for OverTheWire’s ‘Leviathan’ wargame. This is the second OverTheWire wargame I’m trying (after ‘Bandit’). This game is much shorter than Bandit, having only 7 levels, but, unlike Bandit, Leviathan doesn’t have any problem statements or recommended commands – you just log in to the server and find the flag somewhere on it. Leviathan is the second wargame OverTheWire recommends you to play (after Bandit), and the difficulty level is supposedly 1/10. We shall see about that…

Levels

- Start $\rightarrow$ Level 0

- Level 0 $\rightarrow$ Level 1

- Level 1 $\rightarrow$ Level 2

- Level 2 $\rightarrow$ Level 3

- Level 3 $\rightarrow$ Level 4

- Level 4 $\rightarrow$ Level 5

- Level 5 $\rightarrow$ Level 6

- Level 6 $\rightarrow$ Level 7

Start $\rightarrow$ Level 0

ssh leviathan0@leviathan.labs.overthewire.org -p 2223

Level 0 $\rightarrow$ Level 1

I used ls -la in the home directory and found a hidden directory called .backup, and a file called bookmarks.html inside it. bookmarks.html contains many words, so I just tried using

cat bookmarks.html | grep password

and found the password for leviathan1.

Level 1 $\rightarrow$ Level 2

The home directory only contained an executable, check, which prompts the user to enter a password when it is executed. I tried many different ways to crack the check executable, including entering the password for the current level, piping in input, using strings, objdump, nm etc but I couldn’t find anything useful.

I decided to look for a clue in an online walkthrough, and I saw that someone used the ltrace command. ltrace was completely new to me, and it is a command used to trace library calls made during the runtime of an executable. Using ltrace ./check and entering a random string when asked for the password displayed the function which is called to compare the input with the expected password and the expected password itself.

Rerunning check with the correct password gave me a shell as leviathan2. All that was left was to retrieve the password for the next level from /etc/leviathan_pass.

Level 2 $\rightarrow$ Level 3

There was an executable in the home directory called printfile, which prints the contents of a specified file (specified as a command line argument). Of course, the first thing I tried was to use ./printfile /etc/leviathan_pass/leviathan3, but I got the message “You cant have that file…”. I tried printing out some other files like printfile itself and .profile, and their contents were succesfully printed.

Using ltrace I found out that an access() function first checks for read permissions on the file specified as argument. cat is then executed using the system() function.

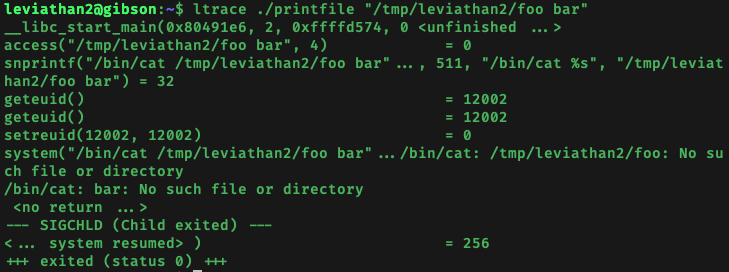

I tried many different formats for the name of the file passed in as argument to printfile, and I discovered something which was useful. I created a file in /tmp/leviathan2 called foo bar (2 words separated by a space), and got the following output from running ltrace ./printfile "/tmp/leviathan2/foo bar":

What we can see is that the although access() checks the entire input string as-is, the cat command which runs at the end splits up the input filename string using the space character as the delimiter. Therefore, even though /tmp/leviathan2/foo bar passed the access() check (because it exists and I had read access), cat is first executed on /tmp/leviathan2/foo then on bar.

I came across the concept of symbolic links (symlinks). As I understand it, a symbolic (soft) link is a file type which points to another file or folder in the system. The file contains a text string (the ‘address’ of the target resource) which will automatically be interpreted by the OS as a path to another resource. Soft/symbolic links differ from hard links in that while the former is just a file containing the address of the target resource, the latter is a link to the actual resource stored in the system.

Therefore, in the /tmp/leviathan2 folder I created a symlink called foo which links to /etc/leviathan_pass/leviathan3 using

ln etc/leviathan_pass/leviathan3 foo -s

Running ./printfile "/tmp/leviathan2/foo bar" resulted in cat /tmp/leviathan2/foo being executed, which, because of the symlink created, is essentially the same as cat etc/leviathan_pass/leviathan3.

Level 3 $\rightarrow$ Level 4

In the home directory I found an executable called level3 which asks for a password when executed. Using what I learned from the previous levels, I used ltrace to peek into the library calls made while level3 executed, and I identified the line of code which checks my input against some string which I figured was the expected password. Rerunning and typing the expected password when asked gave me a shell as leviathan4 which allowed me to easily retrieve the password for the next level.

Level 4 $\rightarrow$ Level 5

In the home directory a found a hidden .trash folder containing an executable called bin. Running it printed a binary string onto the console. Throwing the binary string into an online binary to ASCII convertor (like cyberchef) gave a string resembling a password for a leviathan level (presumably the next one). Attempting to ssh into the next level using this password shows that the string was indeed the password for the next level.

Level 5 $\rightarrow$ Level 6

In the home directory is an executable called leviathan5. Running it gave a message that the file /tmp/file.log doesn’t exist.

I used vim to create the file and add some placeholder text. Rerunning leviathan5 just printed the placeholder text to the console. I realised that the file.log file I just created disappeared, and my guess is that every time file.log is accessed by leviathan5, it is deleted after.

I used a technique learnt earlier and created a symlink in /tmp called file.log which linked to /etc/leviathan_pass/leviathan6. Running ./leviathan5 yielded the password for the next level.

Level 6 $\rightarrow$ Level 7

The home directory contained ./leviathan6, which asked for a 4 digit code as a command line argument. My first thought was to write a script to iterate over all the possibilities in a simple brute force solution. The script I wrote was:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

cd # changes to the directory containing the leviathan6 executable

for ((i = 0 ; i < 10000 ; i++)); do

./leviathan6 $i #tries executing the binary with all possible 4 digit combinations

done

Running it gave me a shell as leviathan7, and I simply looked in the usual place for the password for the next level.

Conclusion

Leviathan7 contains a congratulatory message.

I enjoyed Leviathan much more than Bandit, because it felt like I was really trying to crack binaries instead of just executing certain commands in a particular order.

However, one thing I found odd was that some levels were much, much ‘harder’ than the rest. I probably spent more time on levels 1 and 2 than on the other levels combined (because I wasn’t aware of ltrace and symlinks), but I guess if I had already known about the concepts I would’ve solved it much quicker. Additionally, the techniques used to solve the later (easier) levels were pretty much the same as the earlier (harder) levels, but it served as good practice.